What do you mean? Exploring Joyce’s “underthought” and Wittgenstein’s meaning in language

A beer-laden example

We take much for granted in our everyday communication.

Take for example a simple statement like “Let’s go for a beer”. Taken explicitly, you and I will not “go” for a beer per se, but we both understand the meaning of the statement to be that we will eventually end up at a pub drinking some form of liquid.

There is also a deeper level of inferred meaning related to the context in which the statement is said, also known as connotation. If you and I are in conflict, the statement may mean I intend to reconcile. If I want a romantic relationship with you, the statement may infer a date of some sort. If it is after work, the purpose may be either celebration or resignation. If we don’t know each other and I say this while waiting with you at a crosswalk, I may be intentionally creating an awkward situation.

Yet deeper than this, there may be an unspoken and perhaps unknown meaning behind the statement, similar to the concept of subtext. Perhaps my request comes from a need for validation, for community, or for connection. Going for a beer may be a symbol that all is right in the world or my projection that things are about to become unsettled.

It is to this last level of meaning that we are introduced to the notion of the “underthought”.

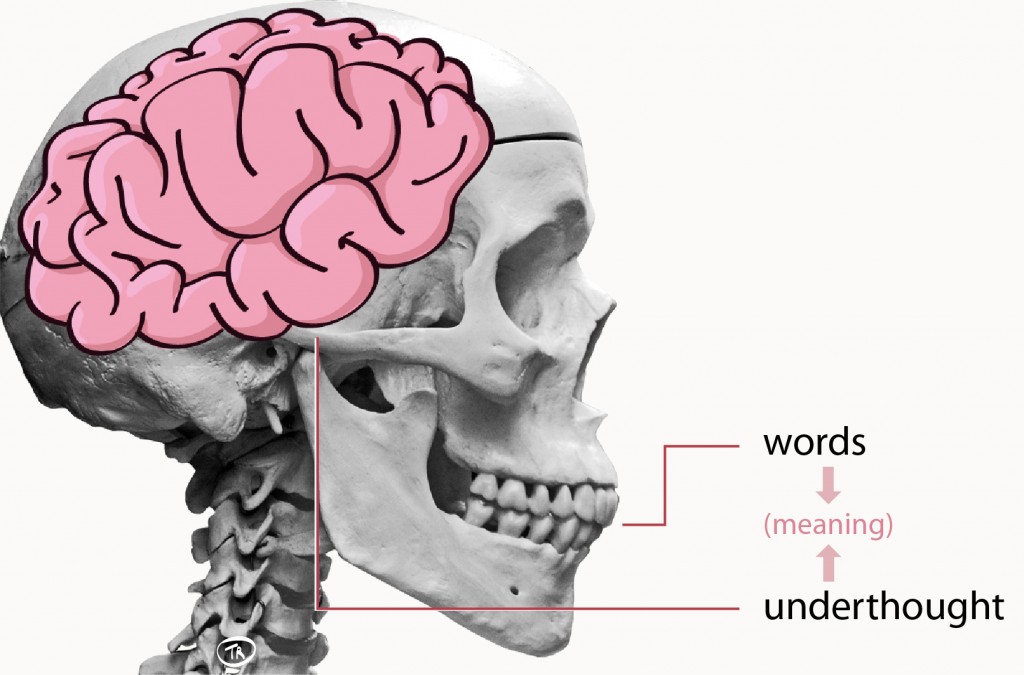

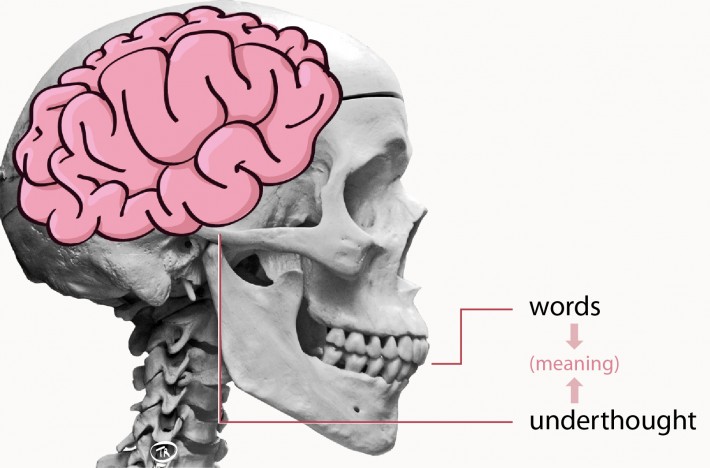

The underthought

I encountered the notion of “underthought” in Mike Harding’s review of Irish novelist James Joyce and philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. The reason for the introduction was my own research into Wittgenstein’s work on the meaning behind language mentioned in a Coursera Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) I am taking from Duke University called Think Again: How to Reason and Argue.

Harding presents underthought as a concept used by Joyce to refer to “the thoughts that the thinker appears to know, but does not wish to acknowledge, at the same time as he is actually responding to them.” and “the half-formed thoughts and sensations that appear to be responded to by the thinker.” We acknowledge and respond to underthought, but are either unable to or we choose not to connect the meaning of the underthought with the words that we use.

This is not surprising, given the potential chasm between underthought and what we communicate. Wittgenstein shares that “the inexpressible (what I find enigmatic and cannot express) perhaps provides the background, against which whatever I was able to express acquires meaning.” He observes that “there is always to be found a dark background, which we are only later able to bring into the light and express as a thought”.

Our efforts to bring the underthought “into light” can be considered from two perspectives. First, as inferred above, we can attempt to uncover the inexpressible; to capture, coax and cajole our hidden thoughts into becoming known as if pushing shifting sands up from the ocean depth.

An alternative perspective is to examine our conversations and our conscious thoughts as if from the top-down. We try to deduce the underthought behind what is observable, like performing a crime scene investigation where we are unsure if a crime has even been committed.

Both situations appear difficult to the point of being unattainable. As a path towards the second perspective, Wittgenstein proposes the following exercise:

“Say a sentence, perhaps “The weather is very fine today.” … Now think the thought of the sentence, but… without the sentence.”

It should also be noted that it is not ideal to be doing this analysis on our own. As Michel Ter Hark notes, “introspection cannot be the way one learns their meaning. Instead, meaning is based on use, on shared practices with others. To support this claim Wittgenstein is cited as saying that inner processes stand in need of outer criteria.” This notion of external input to defining our internal meaning gives credence to our propensity to share in a social setting and participate in mutual introspection.

Practical examples in brands, organisational culture, social media

There are a few practical areas where the notion of underthought may be applied.

Brands

What is the underthought of the brand, the unspoken brand identity or brand personality with which people identify? When you look at a logo, billboard or a television commercial, what is it that is not said? How would the brand be described without using the words and symbols they use to describe themselves?

Organisational culture

Does underthought exist at the organisational level? Is there a collective sentiment that underpins the internal conversations, emails, and communications? What is it that goes unsaid among all this is said? These questions can be answered both internally among staff as well as externally in the communications between organisations.

Social Media

Even as I write this blog post, I question my motivation, and the underthought that hides from my awareness. For every Facebook comment, Instagram picture, LinkedIn update and Twitter tweet, what is the underthought behind the words that are used? What is revealed in the collective voice, and what would it look like if the sentiment were to be repeated without using the words that have been used?

A search for alignment, authenticity and integrity

The concept of the underthought presents an opportunity to make the unknown known, to raise to awareness our beliefs that control and govern our language and actions. Like the beer example, I know what I mean by what I say, but I am not always aware of what drives me to say it.

The opportunity is to become aware of the underthought and to determine the extent that we allow it to control our actions. We can assess the alignment in the three levels between what we say and do, what we mean, and the underthought that drives our inclinations. How well there is alignment will determine our authenticity and integrity. This concept of alignment applies to brands, organisations, and our personal expression, be it in social media channels or face to face.

I welcome your comments on the extent you feel there is a deeper level of thought to the meaning behind your words and actions. The notion for me will be top of mind as I consider the underthoughts that guide my own sideways thoughts.

“Let’s” stop analysing everything coming out of my mouth and telling me where my reasoning is coming from and how to improve my argument. 😛

No really, it’s good stuff. (lol. Analyse that!) 😉

I don’t think I have to go far to understand the underthought there… 🙂