What is culture?

Culture is not a table. I can touch a table. I can take a tape measure to a table and tell you how tall and wide it is. I can put the table on a scale and weigh it. If so inclined, I can choose to move, break, or add to my table. While you and I may debate the finer details of the table, we can come to a consensus that what we are talking about is indeed a table.

Such is not the case with culture. I cannot directly see culture, although I can see the evidence of culture. I cannot put culture on a scale or measure it with a ruler, but people may describe culture as “strong”, “heavy”, or “big”. Perhaps due to this intangible nature, there can be debate about what culture is and whether culture is important.

Culture is what you see

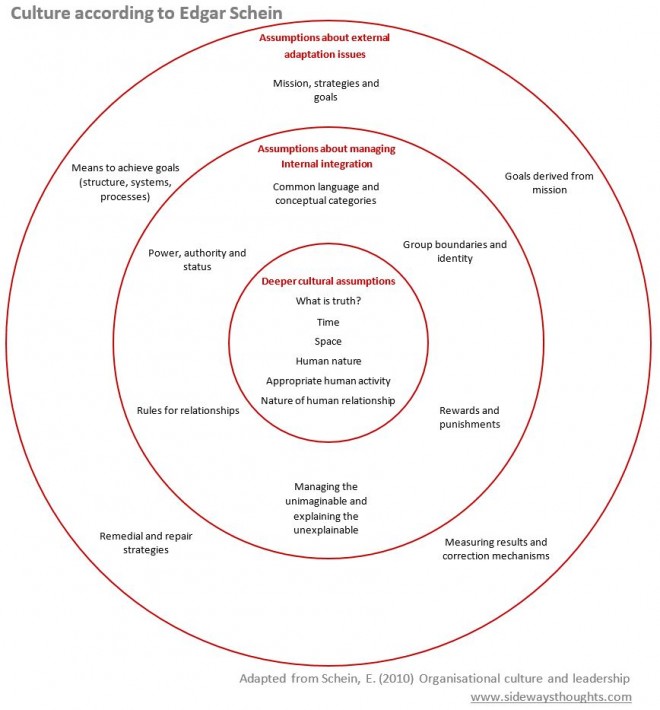

When asked “What is culture?”, we often hear examples of the evidence of culture such as rituals, language used, and dress codes, how space is used, and formal and informal practices. Edgar Schein has a particularly effective depiction of artefacts, espoused beliefs and values, and basic underlying beliefs across three levels, which I previously posted about here.

Defining culture by its characteristics is like defining a table as density, height, and a number of legs. Once known, I can measure those characteristics, saying the table is hard, one metre tall, and has four legs. If I have an end outcome in mind, I might prescribe the best table for a large dinner party, which will be different to my recommendation for a table for my daughter’s doll party. If I am already having a dinner party, I might recommend modifying the table to fit more people.

A similar approach can be taken with culture. I can describe culture in terms of jeans and t-shirts or suits and ties, celebrations when people join or formalised inductions, use of bullying or encouraging approaches to get things done. I might then recommend a more relaxed dress code or tighter controls to change my outcome.

Describing culture by its characteristics tells us what it looks like, but not why culture is important. Leaders can be provided with a list of changes to modify culture and get different outcomes. However, there is a risk that understanding culture based only on what we see will provide a misunderstanding of what culture is and leave an organisation chasing symptoms.

Culture is across multiple boundaries

Another response to “What is culture?” is to point to a group of people who appear to have common beliefs, behaviours and appearances and use that description as an example of culture. This is the perspective initially taken by Dutch psychologist an ex-IBM employee Geert Hofstede as he defined his six characteristics common to national cultures.

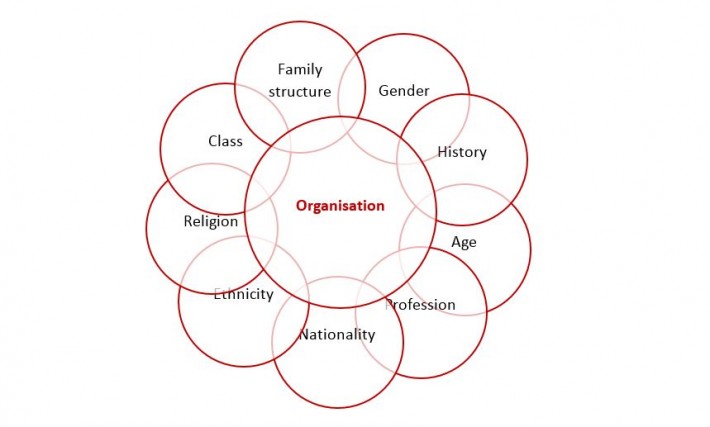

But what is common? Get 100 randomly selected people in a room, and you will likely have groups by gender, age, nationality, ethnicity, industry, profession, religion, class, and more.

These groups may have commonalities, but it may be unhelpful to generalise. Men and women will have varying degrees of chauvinism (explicit superiority) and feminism (advocating equality). Those with religious affiliation will differ by denomination and adherence to practice. An American may be raised in China or someone from India may be raised in Australia challenging national stereotypes. Professionals may share a common approach, but a team of civil engineers may have different culture to structural or mechanical engineers (or so says my daughter from her engineering studies).

These sub-cultures can form at the combination of almost any interface: gender-based business professionals in churches, politicised unions in organisations, nationalities in professions, gender groups in industries, or working teams across organisations. For example, when I managed a 60-person digital agency, we had a client who represented about 60 percent of the work in the studio. The culture of the team working with the client was distinct from the culture of either organisation, which I described in my post on shadow cultures.

Culture can be considered for a group overall, but also needs to take into account the sub-cultures within the group. The number of boundaries created by these sub-groups increases the complexity of understanding what we mean when we talk about culture. It is no surprise then that culture is often confused with other concepts used to describe the intangibles in an organisation.

What is not culture

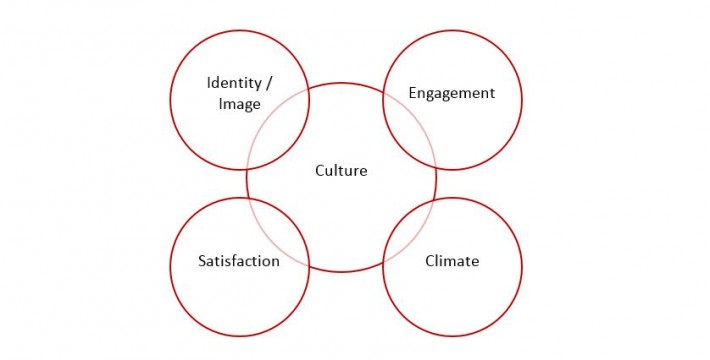

Another way to respond to “What is culture?” is to describe it using other concepts such as engagement, climate, satisfaction, and identity. While these things reflect culture, they are not culture.

Culture is not climate

Climate is a term often used in relation to the weather. This provides a good way to think about climate in organisations.

A recent research paper compared climate and culture, with one conclusion that climate focused on employee perceptions at the time. You can change the climate by announcing a reduction in staff or that the company just won an award. You may see metaphoric tornados rip through the company or people walking around under sunny skies.

You might mistake climate for culture if the CEO is always yelling at staff to get things done, creating storms throughout the business. This will create a consistent climate, but that climate in itself is not culture. A new CEO may change the climate, but he or she may need to address the same challenging culture.

Culture is not engagement

Engagement can be described as how emotionally connected someone is to the group. This is often expressed as how likely they are to stay with an organisation, go above and beyond for the organisation, and recommend the organisation to others. It is from the perspective of the individual (i.e., you would talk about how the employee is engaged, rather than the organisation being engaged).

When comparing engagement with culture, the question becomes one about which one drives the other. While certain cultures are associated with higher or lower levels of engagement, simply focusing on engagement will not necessarily address challenges with culture. Hewitt Associates, an organisation that develops employee engagement and culture surveys, refers to culture driving engagement in a white paper on the difference between engagement and culture. Denison Consulting uses a different culture measure to reflect similar findings about which cultural aspects are likely to result in higher engagement. The distinction that engagement is not culture is highlighted by consultancy Deloitte who feel that engagement may be too limiting a concept.

Culture is not satisfaction

Satisfaction is as it sounds, how satisfied someone is with an organisation. Like engagement, satisfaction can be seen as a result of culture. High employee satisfaction does not mean you have a high performing culture. Indeed, the opposite may be true.

Employees may be satisfied as a result of high pay, work/life balance, and flexible work arrangements. However, they may not be engaged (emotionally connected to the organisation) and the organisation may have a low-performing culture. This is a similar to conditions found in research on servant leadership styles highlighted in the post on different leadership approaches. Leadership styles that focus exclusively on increasing employee satisfaction at the expense of performance can result in satisfied employees in a soon-to-be-bankrupt company. Similarly, driving performance at the expense of satisfaction will not be sustainable. A balanced approach is needed.

Culture is not identity, image or brand

The identity, image or brand is how the group perceives itself and how the group is perceived by others. This is different to culture, in that perceptions of the group from different perspectives are not the same as the common culture experienced by those in the group.

Culture is part of organisational identity, as highlighted by Balmer’s research into the five forms of organisational identity: corporate, communicated, stakeholder perceived, cultural, and envisioned. Similar to engagement and satisfaction, certain types of culture can also result in strong brand positions. For example, the Stengel 50 is a measure of 50 brands that have cultures that espouse a higher purpose and return consistently high performance. Identity, image and brand may reflect culture, but they are not in themselves the same as culture.

The approach to any of these topics is not either/or, but it is important to know the purpose behind the concept you are measuring.

Culture is…

So what is culture? We can talk about the characteristics of culture, consider and compare the different expressions of culture, and debate things that are not culture.

What we have not spoken about is the purpose culture serves. Why does it exist? What does it do for us?

Culture can be described simply as:

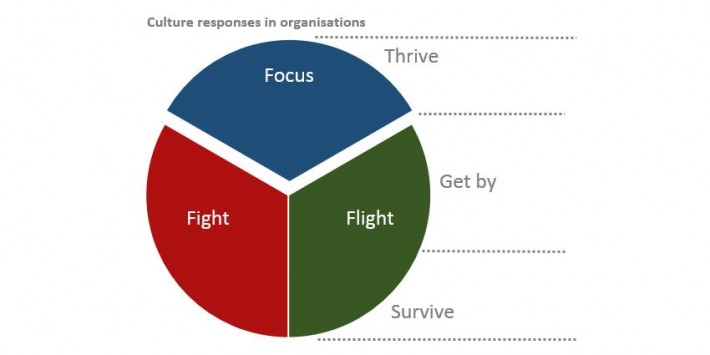

Culture is what we do to survive, get by, and/or thrive.

A description I have found helpful is to refer to culture as a defensive mechanism, although that can have negative connotations. When I previously reviewed defence mechanisms, I was struck by the similarities between personal defences and protective responses we see in organisations. Like individual defences, culture responses can be limiting or beneficial.

Survive, get by, and thrive

Some things are done simply to survive, to feel safe. We avoid conflict to keep our jobs. We dress like everyone else so they we not stand out. We oppose other’s ideas because the ideas are not based on our version of the truth, be it hard data or the popular opinion of influence.

There can be irony in these patterns of thought and behaviour. The defensive responses we feel help us survive and keep us safe can ultimately lead to our demise, either professionally in our career or for an organisation as a whole. Behaviour that helps us keep our job means we never get a promotion and become irrelevant in our industry. Not standing out means we also never get noticed. Needing other’s ideas to conform to ours can limit innovation and stop progress.

Other actions are done simply to get by. We may not be as concerned about our survival, but we get by rather than get ahead and thrive. We do not call out poor performance, as it is easier to avoid conflict and do the work ourselves. We rely on unclear accountabilities to get things done behind the scenes to compensate for inappropriate use of executive power. We operate without a clear mandate and vision rather than holding leaders accountable for providing direction.

And some thoughts and behaviours allow us to thrive. When things go wrong, we have accountability conversations without blame, helping others realise their inherent value. We celebrate success, encourage excellence, and manage performance to a standard of excellence. We deliver to clear goals, while remaining open to feedback and learning as we progress towards those goals.

Fight, flight, or focus

Getting by and surviving is a natural evolutionary response to threat. It is a fight or flight response, or what the culture and personal development approach by Human Synergistics refers to as passive defensive or aggressive defensive responses. These responses are normal, expected and people tend to react between the two as I wrote about in my post on the Life Styles Inventory.

There is third way, however. When I looked up what might be the opposite of fight or flight, one of the more popular responses was research on the impacts of meditation for increasing focus. This word is appropriate, in that the way to thrive, remove fear and thoughts of self-defensiveness is to focus on something outside of yourself. Focusing on a higher purpose or goal is a common theme in research into secure self-esteem, mindfulness, and achieving a state of “flow”. Borrowing on the Human Synergistics’ culture model, the narrative of this focus can be seen in the “constructive” response:

- We know who we are, our boundaries and accountabilities, we own what is ours and let go of what is not, and we are confident and engaged in our purpose.

- We know where we are going, setting clear goals to get there, and learning from our progress.

- We see the value and potential in people, regardless of what they can do for us, and encourage them to realise that value.

- We work with and through the work of others.

Culture is important

A table lifts things up at the right height so we can do what we need to do. If we start here, then we can expand our thinking to what will help us achieve our outcomes. A bench can become a table, and a sit-down dinner may become a stand-up affair to better build community and relationships.

Knowing what culture is, the purpose it serves, helps you recognise the culture of your team and create the kind of culture that will serve your goals. Rather than attempting to address the symptoms, taking a holistic approach to measuring, talking about, and changing culture can expand thinking an help us get more of what we want and less of what we don’t want.

Are you or those you lead surviving, getting by, or thriving? Are the assumptions, thoughts and behaviours protecting security with fight or flight, or is there a focus on a cause greater than individual self-preservation? If you and those you lead can answer these questions, you will know your culture.

If culture is an area of focus for you, I would love to hear your perspective in the comments below.

1 thought on “What is culture?”

Comments are closed.