What is your capital? Principles for investing more than your money

The value of capital

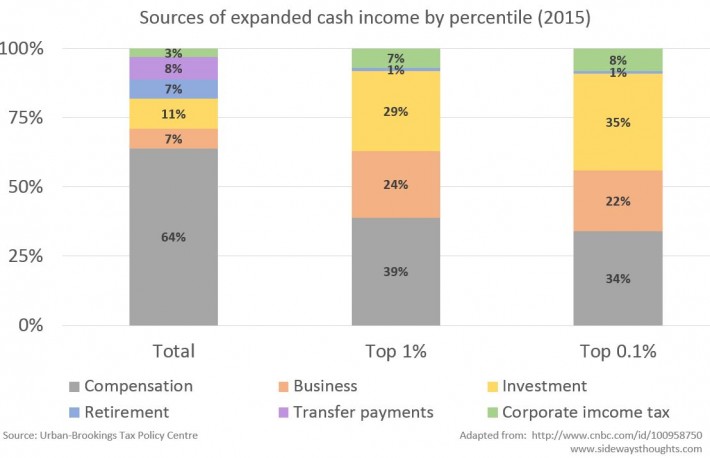

People who are financially wealthy make their money differently than everyone else. The top 1% of wealthy individuals earn over half of their income from business and investment and just over a third from some form of compensation such as salary. This is compared to the total population who earn 18% of their income from business and investment and over half from compensation.

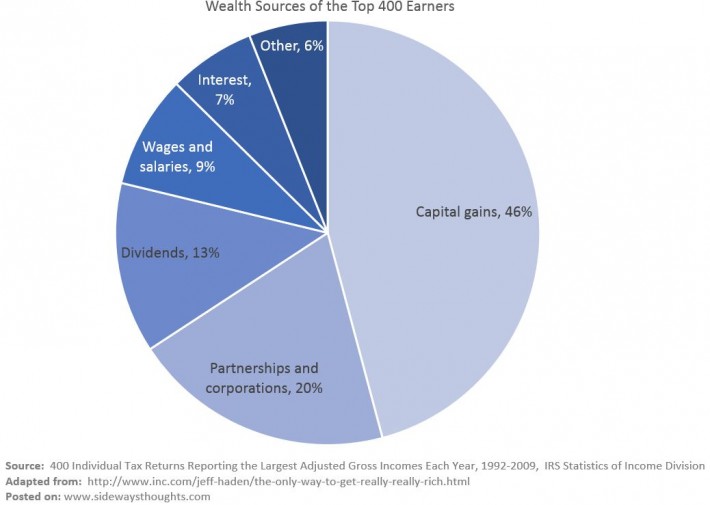

This same pattern is reflected in data from the Internal Revenue Service, which shows that the top 400 earners get 79% of their income from capital gains, partnerships and corporations, and dividends, and only 9% from wages and salaries.

The graphs above appear to highlight two ways to produce wealth. One way is through some form of compensation, such as a salary or hourly wage – a transaction for services rendered. The second way to produce wealth is through the return on some form of capital that is owned, such as property, business, or other investments. Looking at the numbers, it seems that owning capital has a tendency to produce greater volumes of wealth.

Defining capital

So what do we mean by capital? To get an understanding, I figured a good place to start would be to learn from someone who has spent a long time thinking about the concept. In his book Capital in the Twenty-first Century, French economist Thomas Piketty explores capital from the perspective of inequality in multiple countries over several centuries.

Piketty’s observation on the value of capital supports what is hinted at by the graphs:

“The advantage of owning things is that one can continue to consume and accumulate without having to work, or at any rate continue to consume and accumulate more than one could produce on one’s own.”

Characteristics of capital

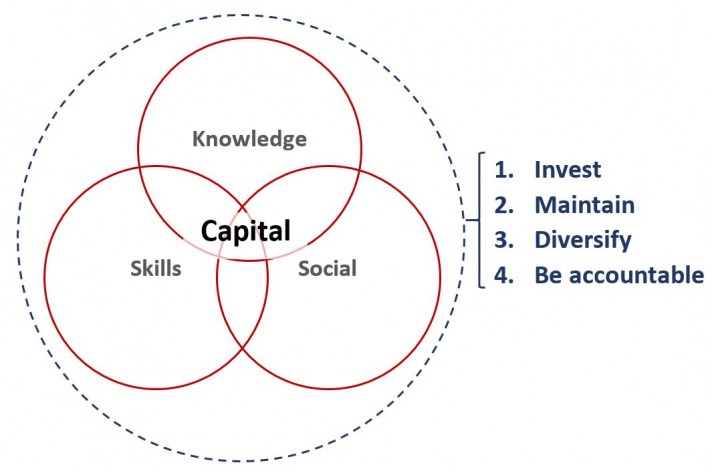

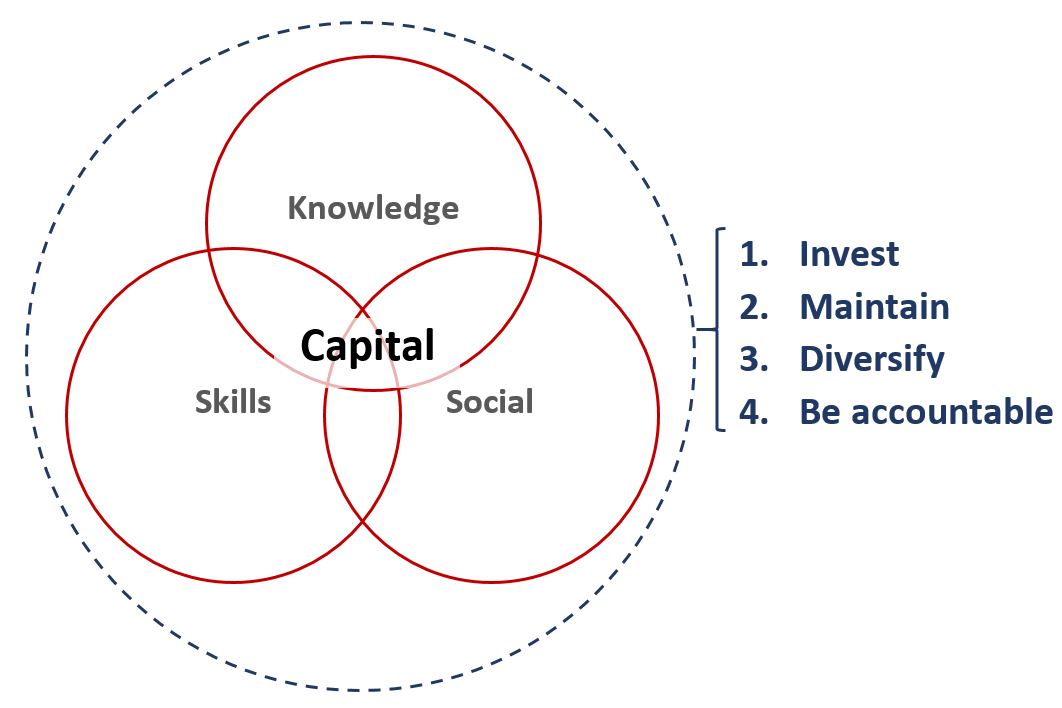

There may be value in taking an intentional approach to our capital, even if that capital is not financial. For example,

- Knowledge capital

Do you have information about a particular field or topic and the ability to apply that information for the benefit of others? - Skills capital

Do you have a way of doing things in a particular industry or domain that enable you to do those things better or faster in the future? - Social capital

Do you have relationships with others, where the strength and/or number of relationships allow you to get things done better than if you were to do it individually?

Just as there is a distinction between earning a salary and owning financial capital, there is also a distinction in whether you are building knowledge, experience and social capital. In his book, Pikkety points out that:

“Capital is never quiet: it is always risk-orientated and entrepreneurial, at least in its inception, yet it always tends to transform itself into rents as it accumulates in large enough amounts – that is its vocation, its logical destination.”

This statement highlights two criteria of capital:

- It involves risk; and

- It has the potential to produce “rents”, or a return on the investment.

If there is little risk involved, or if what you are doing is unlikely to result in a return down the track, then you may not be building capital.

For example, consider the risks involved in earning a wage for time spent. You know that for every hour you spend, you will get paid for that hour. There may be risk in the security of the arrangement, but so long as the arrangement is in place you will receive income.

If, however, you invest energy outside of what you are getting paid for, you are making an investment into your own capital. You may or may not see a future return on your capital in the form of wage increase, career progression, or additional responsibility.

When I coach professionals in business, there can be frustration when they realise that their past investments above and beyond their salary did not result in the rate of return they expected. The stress, sacrifice, professional development, and favours given have not produced a yield, and their proverbial stocks are now trading lower than when they started. Those who have advanced in their career or successfully changed careers have almost always done so through an additional investment on top of what was required of them.

I find framing life investments as capital can help focus attention and provide a break-through in personal decision-making. I share with you a few principles that may help you in developing your own capital:

1. Invest in your capital

Define your capital and set aside investment. If you are investing in a particular knowledge capital, set aside time each week for that investment. For social capital, maintain relationships where you want to have an impact. An investment in skills capital may require volunteering outside of paid work. Be intentional about it, just as if you were setting aside a portion of your paycheck.

Invest without expecting immediate return. Like money, investments in other forms of capital happen not in one lump sum for immediate pay-out, but small investments over time for cumulative return. As the adage says:

“The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The next best time is today.”

Give as though you always have enough (the abundance principle). There is a paradox that plays out in life, in that those who hold tight to their resources often have the least whereas those who give of themselves always seem to have enough. Invest in knowledge to share, invest in social and community to help, and invest in skills to build for others.

2. Maintain your capital

Imagine a house – a form of property capital – has fallen into disrepair. The gutters are leaking, the paint is wearing thin, and the foundation is giving way. The longer the house goes without maintenance, the greater the investment that will be required to get it back to fair market value.

The same goes for other forms of capital. Ten years ago I had competent programming skills in computer languages that are no longer around. Building that capital again would be akin to demolishing the house and starting over. The rapid changes in knowledge and skills requirements means you need regular investments in these areas to maintain your capital.

Social relationships also require regular maintenance. Invest in your relationships. Give without expecting a return. Catch up simply to hear what other people are up to and where you can add value. Imagine a world where a focus of any meeting was seeing how each person could add value to others around the table. Build your community, as in the end that is what has real value.

3. Know where you are building your capital and diversify

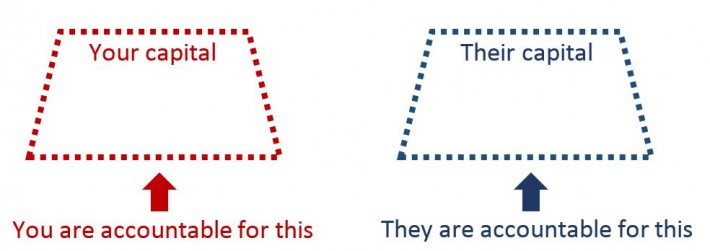

Like a house on a block of land, your knowledge, skill and social capital sits on real estate. You should be aware who owns the real estate on which you are building your capital.

Some people spend their careers building capital for whoever employs them. They are then at risk when they are told their services are no longer required and realise they have left all their capital in someone else’s property. Others may want a career change, but need to build knowledge, skill, and social capital in another area to create a space to move into.

Building your own capital is not being disloyal to your employer; it is being responsible for yourself, which in turn makes you more valuable to whoever you work with and for. This can often be realised with a slight change in intention and an investment of energy on top of what is required.

For example, let’s say you are involved in delivering a project (we will try to generalise as much as possible and say it can be an engineering project, a change project in your organisation, an IT project, or anything that has a start and finish date). You may define success as simply getting paid for completing the project. You would then be building capital for whoever benefits from the project outcomes and whoever receives the benefit from the experience increase in the project team.

Alternatively, do you have an interest in a knowledge area you can spend time researching to raise your own awareness in your part of the project? Can you seek out new skill areas to develop on the side related to the project? Are there other people or communities in your industry who have completed similar projects you can connect with to share lessons and expand your network?

Doing these things allows you to diversify, creating connections and expanding your knowledge in a capital real estate that you own.

4. Be accountable for your capital

You are accountable for building and maintaining your own capital. The last time someone was accountable for building your capital for you was your parents sometime in your early teens. This unfortunately does not happen for many people, as parents generally pass on to their children whatever approach to capital as was passed on to them by their parents.

Your employer is not accountable for building your personal capital. Your employer is accountable for building the capital in their organisation. This may include human capital (acknowledging that as the awkward term that it is), as highlighted by the likes of the Deloitte report on annual trends in human capital. However, that accountability is only in relation to the extent that people help the organisation achieve its goals.

Your partner is not accountable for building your personal capital. They, like you, are accountable for their part in a loving relationship. They may provide support for you and create an environment where you both can grow and develop, but that does not extend to building your capital for you.

There are also professions such as psychologists, teachers, and coaches whose roles are to help you build your personal capital, much like an architect might help you design a house, an investment adviser may help you grow your bank account, or a management consultant may help you build your business. Ultimately, however, their accountability ends at showing you the way.

Once you accept you are the only one who is accountable for building your capital, then you can start making choices about where you want to play.

What is your capital?

The tax offices indicate that those who make economic investments in capital have potential for greater financial wealth. The same appears to be true for other forms of capital like knowledge, skills, and relationships.

With this in mind, what are some areas where you could build capital?

Taking a capital perspective can be challenging but is also exciting. As Pikkety noted, capital is risk-orientated and entrepreneurial, but this is part of the appeal. Building your capital makes you feel alive, and you want to share the experience with others who are on the same journey.

Once you start the conversation, you can expect to attract like-minded people. Using my own life as an experiment, capital conversations have resulted in three exciting start-up projects where I partner with great entrepreneurs to invest our various forms of capital for great potential. I also find I am having more conversations that result in the building of other’s capital.

Based on these experiences, my hope in writing this is that a capital perspective might help you with where you invest your time and energy. If you feel others might benefit from a capital mindset, please feel free to pass the message on through the links below. If you have your own capital building stories, I would love to hear about them in the comments at the bottom of the post!

Aa-hah!!

That is what I have been needing to know, it puts what I have been doing and still need to work on in a nice clear perspective. Thanks, Chad!