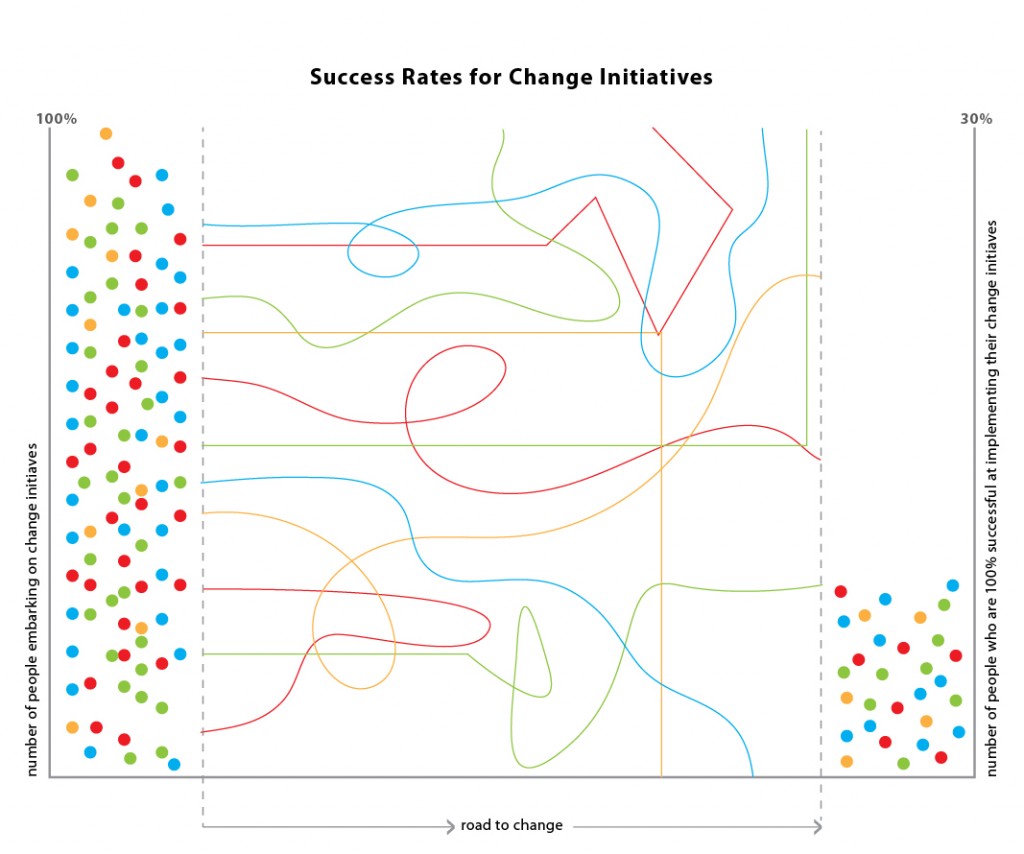

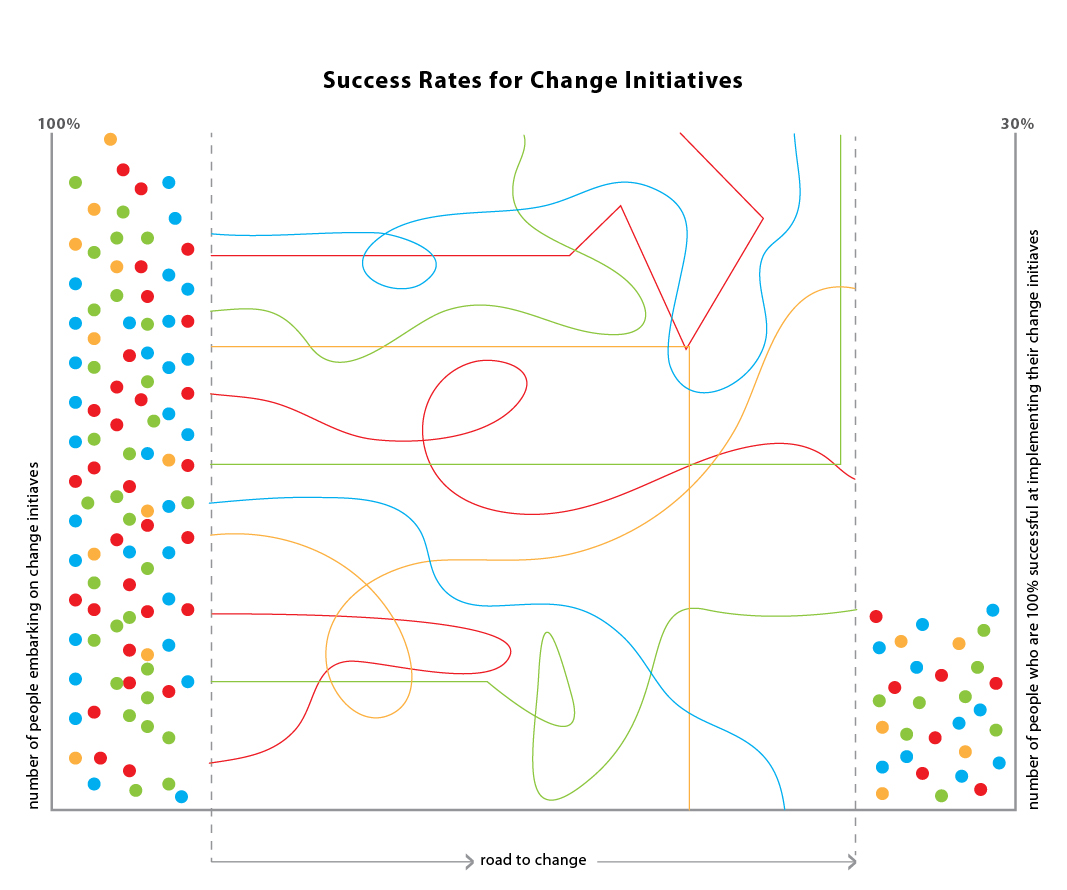

Seventy percent of change initiatives fail: Borrowing Tolstoy to question our definition of progress

Change failure rates appear to be unchanging. Perhaps we should not be looking at how we change, but focus on what we are changing towards in the first place.

Exploring failure

The seventy percent failure rate statistic is often referenced to material by Kotter in the early-90s. The exact research behind the number is difficult to trace, but the general trend appears to be consistent with current studies:

- Only thirty percent of 1,546 executives rate their change initiative successful (Keller & Aiken, 2008).

- Research into isolated business aspects reflect similar outcomes, with an eighty-eight percent of IT projects failing to be delivered on time and on budget (The Standish Group, 2009).

- Seventy percent of mergers and acquisitions failing to achieve desired outcomes (Weber & Camerer, 2003).

If the cliché of “change is a constant” is true, then the above findings indicate that change failure is also constant. This failure is profitable from some, evidenced by over 7,900 books retuned with a search for “organisational change” on amazon.com and an Australian AU$8 billion consulting industry that experiences consistent 2.1 percent growth (IBISWorld, 2011). We as the collective commercial collaboration of market forces appear to be taking the same approach to change and getting the same results.

Frameworks by authors such as Collins and Peters are based on companies that go from “good to great” or have “excellence”. Consulting and academic industries are cannibalistic, with critics of such approaches putting pen to paper as soon as the material is published and lie in wait for highlighted companies to no longer be great or excellent. Such failures spawn even more models of between 5 steps to 163 points for the weary organisational leader to supplement what previously did not work.

The scenario above raises many questions. Are the volumes of collective change approaches inadequate? Are business leaders incompetent, ignorant, or wilfully not heeding the advice? Is there a conflict of interest in paid consultants and keynote-speaking academics both measuring failure rates and prescribing solutions? These questions are for a later post.

The question I ask now is more esoteric. What if the issue is not the change process, but what we are changing towards?

Change ourselves to change our view of progress

The definition of success or failure is entirely relative to the one assessing the outcomes. Hitler’s failure was a success for collective world powers. A successful rebrand of a large oil company could be seen as failure to environmentalists and a neutral outcome to consumers trapped in their over-reliance on fossil fuels. The failures of the global financial market are felt in corporate accountability and irresponsible consumers, but the failure could be seen as a success if viewed at a macro-level if it results in a realignment of market forces.

The majority of change in organisations is towards the notion of progress. Progress is typically defined as growth, and this growth is generally characterised by increases in revenue, profit, staff count, geographic spread, and political influence. I am not the first to question the emphasis of our change initiatives.

Tolstoy faced these same questions in the 1850s. At around the age I am now, Tolstoy observed an execution by guillotine when visiting France, observing “the sight of an execution [by guillotine] revealed to me the instability of my superstitious belief in progress”. To repeat a point by another blogger, Tolstoy states “therefore the arbiter of what is good and evil is not what people say and do, nor is it progress, but it is my heart and I”.

Seventy percent failure rates seem shocking. History has done nothing to show me these will change. If we were to reassess the outcomes as measurements of the personal character of those involved in the change, I wonder if the measurement would be substantially higher.

Borrowing Tolstoy, I become more convinced that change success or failure is measured not in the progress towards commercial outcomes but in the character of those involved in the change. To be blunt and avoid hiding behind academic observations, I acknowledge the responsibility for what it is I change towards is within “my heart and I”.

good stuff